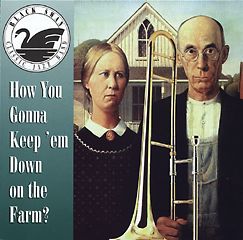

How You Gonna Keep 'Em Down on the Farm

This recording is no longer available for purchase.

This recording is no longer available for purchase.

"How You Gonna Keep 'em Down on the Farm?" was recorded at Gung Ho Studios in Eugene, Oregon on February 28 and March 1, 1998. This is the first recording with vocalist Marilyn Keller, featured on seven numbers, and includes 17 arrangements of songs composed between 1899 and 1938.

The musicians on this recording are as follows:

- Marilyn Keller, Vocalist

- Ernie Carbajal, Trumpet

- John Bennett, Piano

- Steve Matthes, Clarinet

- Glenn Koch, Washboard

- Don Stone, Trombone

- Ron Hinkle, Banjo

- Kit Johnson, Tuba

Liner Notes

The original liner notes read as follows:

How You Gonna Keep 'em Down on the Farm

The era in America stretching from 1900 through the 1930s -- that is, from the last days of the Gay Nineties through World War I and into the Great Depression that ended only with our entrance into World War II -- saw an unprecedented transformation in our music. In this brief span of time, ragtime appeared and became a national obsession. Stride, boogie-woogie, New Orleans jazz, and the blues gained national and worldwide popularity. And by the mid-1930s, big bands were assimilating these styles into what we now call swing. It was an incredible burst of energy that produced this thing that we loosely call jazz -- and it was drawn largely from the experience of black America.

The selections contained here are by some of the most respected and emulated composers and performers of this unique period of creativity: Eubie Blake, Louis Armstrong, "Jelly Roll" Morton, W.C. Handy, Duke Ellington, to name just a few. Eubie Blake's Charleston Rag comes from the beginning of this era. Two selections from the 1930s, Ellington's It Don't Mean a Thing and Porter's My Heart Belongs to Daddy, represent the vocal side of jazz and are the most recent works on this recording.

If there is a star performer on this CD, it is our vocalist, Miss Marilyn Keller, one of the most sought-after performers in Portland's jazz and gospel settings. Her renditions are superb -- especially Morocco Blues. This piece will haunt you. Among her other selections are two hits from Broadway musicals, Eubie Blake's My Handy Man and Cole Porter's My Heart Belongs to Daddy. These fit well into Marilyn's stylings, as does the Ellington piece, It Don't Mean a Thing.

But the most energetic -- "rambunctious" may be a better word here -- is our title tune, How You Gonna Keep 'em Down on the Farm, and it may be a bit prophetic. Soldiers, eager to return to the States from European duty at the end of World War I, were not going to be content with the quiet life back at home. In fact, the entire population was being reenergized and pushing the country into the decade known as The Roaring Twenties -- the Golden Age of Jazz.

We hope your spirits will be reenergized, too.

Music

My Handy Man. 1930.

Eubie Blake, Andy Razaf. Arr., John Bennett. Vocal, Marilyn Keller. This song was featured in the show, Blackbirds of 1930. It is one of the best of the double-entendre songs, in which the intent is to convey meanings in polite language that are usually quite risque.

Coal Cart Blues. Louis Armstrong. Arr., Kit Johnson. Although titled as a blues, this two-theme piece really jumps.

Mister Jelly Lord. 1923. "Jelly Roll" Morton. Arr., John Bennett. First recorded by the New Orleans Rhythm Kings with Morton, this song has pretty melodies for both its verse and chorus. In 1923, the Levee Serenaders, a Morton group, recorded this, as well.

Ragtime Nightmare. 1900. Tom Turpin. Arr., John Bennett. At the turn of the century, Tom Turpin's Rosebud Bar in St. Louis was the mecca for underground ragtime musicians. Tom was so ample in girth that he had his piano raised on blocks, enabling him to play standing up, as his stomach got in the way when seated. He and his brother, Charles, also ran dance halls and gambling and sporting houses.

Farewell to Storyville. Clarence and Spencer Williams. Arr., Kit Johnson. Vocal, Marilyn Keller. Storyville was the area in New Orleans set aside as a red-light district. Saloons and sporting houses, as well as musicians, flourished here. But with the entry of the U.S. into World War I in 1917, the Navy forced the city to close the doors on these establishments because too many sailors were catching diseases or being mugged or knifed there. The musicians and girls who worked in Storyville headed up river to find work in places like St. Louis and Chicago.

How You Gonna Keep 'em Down on the Farm. 1919. W. Donaldson, S. Lewis, J. Young. Arr., Kit Johnson. Vocal, Marilyn Keller. Returning from World War I, after time off in Paris, many soldiers found that raking and plowing back home on the farm was a bit dull. This arrangement comes with authentic sounding barnyard serenades -- but no smells. The movie, For Me and My Gal, with Judy Garland and Gene Kelly, featured this number.

Charleston Rag. 1899. Eubie Blake. Soloist, John Bennett. Eubie was 16 when he composed this piece, although he didn't write it down until 1915, when he was studying composition. He called this a rag, but it has more features of stride piano. By the age of 15, Eubie was playing in the bars around town -- and sneaking out of the house to do it. When his mother got wind of this, she was upset and told Eubie, "Just wait till your dad gets home." His dad, however, softened his stance, when Eubie showed him how much he was earning.

Wild Man Blues. 1927. "Jelly Roll" Morton, Louis Armstrong. Arr., Lu Watters, Kit Johnson. The original title was Ted Louis Blues. Armstrong is listed as co-composer of this piece because he recorded a slightly different version with Johnny Dodds Black Bottom Stompers somewhat later than the 1927 version by Morton and his Red Hot Peppers.

Tres Moutarde. 1911. Cecil Macklin. Arr., John Bennett. Vocalist, John Bennett. "Tres Moutarde," or "Too Much Mustard," as the song has it, was one of the featured tunes played during World War I by James Reese Europe's Concert and Marching Band. This band was one of the first to bring the syncopated rhythms of ragtime and jazz to European audiences. Mae West, who expressed the notion that "too much of a good thing was wonderful," may have disagreed with this song's sentiment. Too Much Mustard made the beans in the pot -- as well as kissin' -- too hot.

Frog-i-more Rag. 1918. "Jelly Roll" Morton. Arr., James Meyer. Morton may have borrowed the opening theme, a chromatically rising passage, from a certain pianist, Benson "Frog Eye" Moore, hence, the title. The phrasing and chord progression are vintage Morton.

My Heart Belongs to Daddy. 1938. Cole Porter. Arr., John Bennett. Vocal, Marilyn Keller. Largely because of Mary Martin's rendition of this song and the girlishly modest striptease that went with it, this piece became the big hit of Porter's Leave It to Me. This musical spoofs the bungling efforts of the U.S. diplomatic corps in Russia during the Stalin era. Mary Martin made this number her theme song.

It Don't Mean a Thing. 1932. Duke Ellington. Arr., John Bennett. Vocal, Marilyn Keller. This was originally written as an instrumental piece. When Ellington began his collaboration with the publisher and promoter, Irving Mills, words were added. The piece foresaw the Swing Era by at least three years with that word in its title.

Temptation Blues. Joe "King" Oliver. Arr., Steve Matthes. "King" Oliver was the foremost cornet player in Storyville before it closed. Later in Chicago, he was the most direct and decisive influence on Louis Armstrong.

The Cat and the Dog. 1928. Harry Reser. Soloist, Ron Hinkle. This novelty rag is considered one of the best by the famous banjo player, Reser.

Buffalo Blues. 1928. "Jelly Roll" Morton. Arr., Doc Evans, Kit Johnson. The first title of this piece was Mister Joe. The Johnny Dunn Band recorded this first, and it was probably one of the favorite numbers of the Joe Oliver Creole Jazz Band.

Morocco Blues. Joe Jordan, Clarence Williams. Arr., Steve Matthes, Kit Johnson. Vocal, Marilyn Keller. After a successful career in New York as a composer and arranger of songs, rags, and musical revues, Jordan retired from music and went into real estate in Chicago, where he became rich several times over. Clarence Williams spent his working life as a band leader and in the publishing business.

Yellow Dog Blues. 1914. W.C. Handy. Arr., Kit Johnson. Vocal, Marilyn Keller. Riding on that "Southbound Rattler Side Door Pullman Car" was one way of describing travel by rail in an empty boxcar.